Floods, storms, and extreme temperatures kill many people around the world each year. But the deadliness of these climate hazards changes as the climate warms, populations grow or move, and societies invest, or fail to invest, in infrastructure and emergency response.

Understanding whether these events are becoming more or less deadly is essential for assessing preparedness and reducing future mortality. A new study published in Geophysical Research Letters takes a careful look at this question and finds a mix of progress and growing risk.

The study, led by B. B. Cael, assistant professor in the Department of Geophysical Sciences at the University of Chicago, analyzes nearly 2,000 of the deadliest climate hazard events worldwide since 1988 using data from EM-DAT, the largest public database of disaster-related deaths. Rather than focusing on individual catastrophes, the research uses a statistical approach designed to reveal longer-term patterns while accounting for the extreme variability that characterizes disaster mortality.

“The deadliness of climate hazards reflects more than just the weather,” Cael said. “By looking across decades of data, we can see how changes in exposure, vulnerability, and preparedness are shaping risk over time, alongside climate change.”

One of the clearest signals in the data comes from Asia. The study finds that floods and storms in the region have become both less frequent and less deadly since the late 1980s. The most plausible explanation is reduced vulnerability driven by development, improved infrastructure, early warning systems, and more effective emergency response. Using a conservative estimate, the analysis suggests that these changes have saved about 350,000 lives.

While floods and storms remain serious threats across Asia, the results show that sustained investments in preparedness can translate into large and measurable reductions in mortality.

However, in Africa, deadly floods and storms have become more frequent, a trend that appears to be driven mainly by population growth in flood-prone areas. As more people live in vulnerable regions, exposure increases, raising the mortality rate when floods occur. The analysis also places recent disasters in a longer historical context.

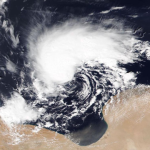

Storm Daniel, a Mediterranean cyclone that struck in 2023 and caused catastrophic flooding in Libya, was Africa’s deadliest storm on record. Statistically, the study finds that an African flood or storm of comparable deadliness would be expected only once every few centuries.

Temperature-related hazards show another kind of shift in Europe. Deaths linked to extreme temperatures have increased, largely because heatwaves have become more common relative to cold extremes. This pattern reflects how climate change can alter not just how often hazards occur, but which ones pose the greatest threat to human health.

Taken together, the findings show that climate hazard mortality is not moving in a single direction worldwide. In some regions, reduced vulnerability has saved hundreds of thousands of lives. In others, growing exposure and rare but devastating events continue to drive losses. The study highlights the importance of continued, systematic monitoring of disaster deaths, both to understand how risks are evolving and to learn where interventions are working.