By Hemant Kumar Rout

Doorstep delivery of treated drinking water is one of the most cost-effective ways to achieve near-universal adoption of safe water and offers a practical and scalable alternative to piped supply that often remains unsafe, a new study has stated.

The study conducted across rural Odisha by three US-based researchers from University of Chicago and University of Warwick revealed 76 per cent of the surveyed households used groundwater for drinking, 34 per cent used piped water and less than one per cent reported using surface water or bottled water.

While many households recognise that their drinking water is unsafe and they try to treat it, such measures are often irregular. During the survey, 13 per cent of households reported using chlorine at least once, 19 per cent boiled water at least once and 39 per cent strained water. On average, households spent 32 minutes per day collecting drinking water, adding to both drudgery and lost labour time.

The research, carried out in partnership with Spring Health Water and covering nearly 60,000 households across 120 villages, showed that simple, localised water treatment combined with home delivery can dramatically expand access to clean drinking water in the state where contamination of groundwater, surface water and even piped supply is widespread.

The researchers also experimented with three models to understand how much households value clean, treated water delivered to their doorstep. When water was free, more than 90 per cent of households chose to order it. Even at a low price of 14 paise per litre, take-up remained at 89 per cent, nearly double the adoption rates typically seen for chlorine tablets, even when provided free.

“Our research shows that the goal of providing safe drinking water that is convenient to access can be achieved without relying on expensive pipe infrastructure,” said study co-author Fiona Burlig, an assistant professor at the Harris School of Public Policy.

“The approach we tested appears to be economically sustainable, with people willing to pay more than previously thought. It also delivered measurable health benefits for a population where waterborne diseases remain a significant threat,” she said.

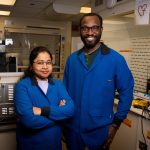

Burlig and her co-authors, assistant professor Amir Jina and University of Warwick professor Anant Sudarshan conducted the study in 120 villages, where water treatment plants powered by solar energy have been set up to provide safe drinking water.

“We observed that one approach to bring clean water to the poor is to literally deliver it to them. Small rural companies are increasingly providing this service but not at prices that most households can afford. Households value safe water and can afford it at discounted prices. The government can think of subsidising it for wider coverage to address public health challenges,” Sudarshan said.