As world leaders enter climate talks, people in poverty have the most at stake

By Melina Walling and Eléonore Hughes

RIO DE JANEIRO (AP) — When summer heat comes to the Arara neighborhood in northern Rio, it lingers, baking the red brick and concrete that make up many of the buildings long after the sun has gone down. Luis Cassiano, who’s lived here more than 30 years, says he’s getting worried as heat waves become more frequent and fierce.

In poor areas such as Arara, those who can afford air conditioning — Cassiano is one — can’t always count on it because of frequent power outages on an overloaded system. Conditions were so unbearable for Cassiano that he installed a green roof about a decade ago that can keep his house up to 15 degrees Celsius (about 27 degrees Fahrenheit) cooler than his neighbor’s. But the heat still makes him extremely uncomfortable, he said.

“The sun in the summer nowadays is scary,” Cassiano said. And a lack of green spaces makes the heat worse.

“Here we don’t have any parks, gardens, green engineers, experts in environmental matters. They go to Rio’s richer parts,” Cassiano said. “It’s negligence. We respond practically on our own.”

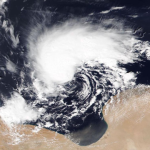

As world leaders come to Brazil for climate talks, people like Cassiano are the ones with the most at stake. Poor communities are often more vulnerable to hazards like extreme heat and supersized storms and less likely to have the resources to cope than wealthier places.

Any help from the climate talks depends on countries not just laying out pledges and plans to lower emissions. They also need to find the political will to implement them, as well as come up with the billions of dollars needed to adapt everything from harvests to houses to better withstand human-caused climate change.

All of it is sorely needed for the 1.1 billion people around the world who live in acute poverty, according to the United Nations.

That’s why many have lauded the choice of Belem, a relatively poor city, to host these talks.

“I am pleased that we will be going to a place like this, because this is where climate meets poverty, meets demand, meets financing needs, and meets the reality of the majority of the population of this world that are impacted by climate change,” said Inger Andersen, executive director of the U.N. Environment Programme.

Even in wealthy countries, the poor face climate impacts

It’s not just poor people in poor countries who suffer when poverty and climate change collide. A U.N. Development Programme report found that even in highly developed countries, 82% of people living in poverty will be exposed to at least one of four climate hazards: high heat, drought, floods and air pollution.

People in poverty are more vulnerable to climate change for several reasons, said Carter Brandon, a senior fellow at the World Resources Institute who works on the economics of climate change and the finances of adapting to it.

They might not have the money to leave areas like inundated deltas or floodplains, landslide-prone hillsides or farmlands regularly scorched by drought. Nor to rebuild after a disaster hits. And those financial hits can be worsened by other problems like health issues, lack of education or lack of social mobility.

“It’s not just, climate destroys buildings or bridges or property. It destroys the livelihoods of families. And if you don’t have savings, that’s really devastating,” Brandon said.

Crop yields suffer in many places, but worst in poor countries

Even relatively developed countries with more ways to adapt will see some farm yields drop significantly, according to a UNDP analysis of global agriculture under different warming scenarios.

But poorer countries will be more severely affected, said Heriberto Tapia, head of research and strategic partnerships advisor at the UNDP Human Development Report Office.

Tapia said Africa, with more than 500 million people in poverty, is a big concern. Many depend on crop yields for their livelihoods.

Most of the world’s 550 million small agricultural producers are in low- or middle-income countries, working in marginal environments and more vulnerable to climate hazards, said Ismahane Elouafi, executive managing director of CGIAR, the Consultative Group for International Agriculture Research.

Elouafi thinks technology can help ease the climate pressure on many of those farmers, but also noted that many can’t afford it. She’s not confident that this year’s COP will provide enough money to help with that.